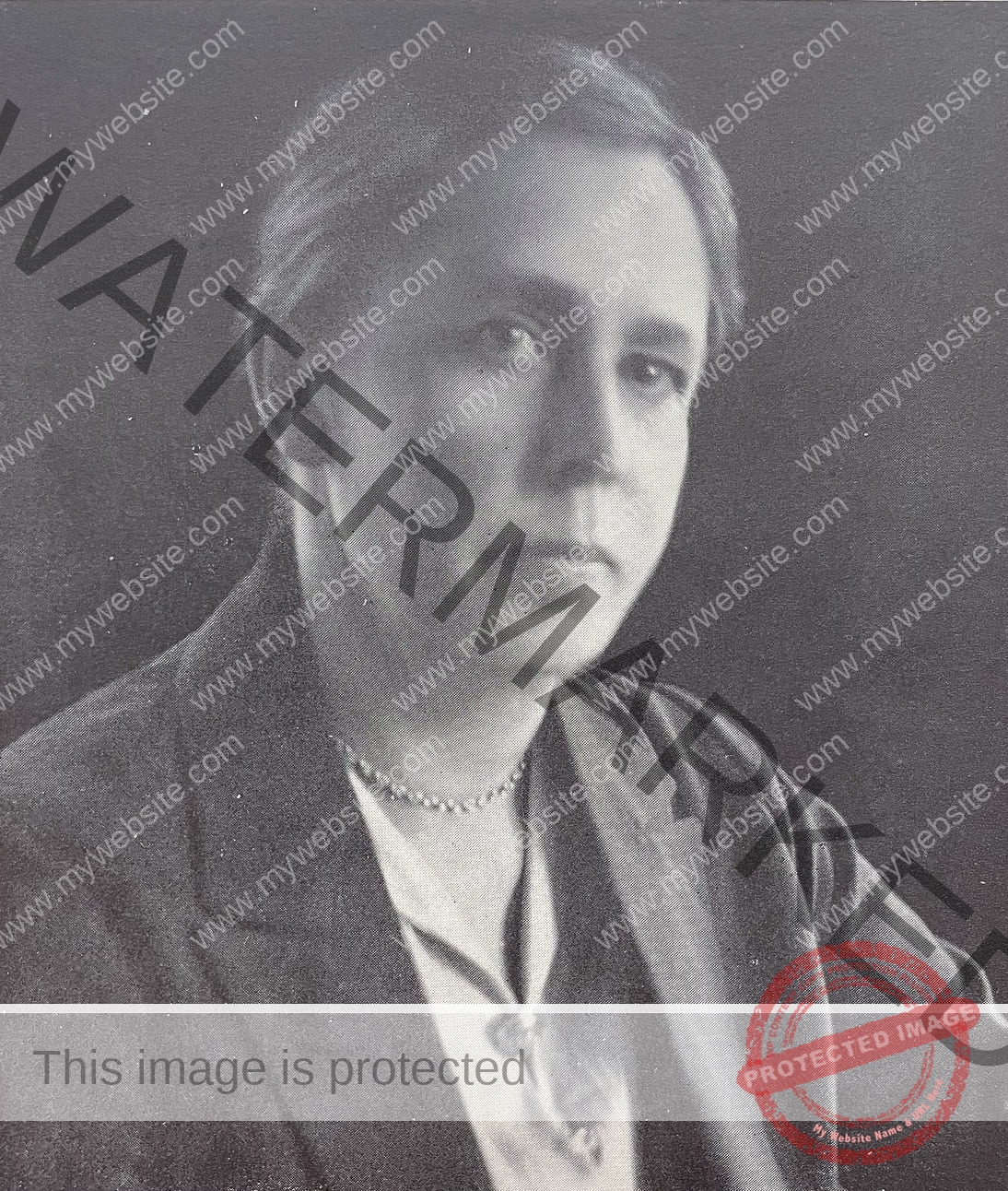

Margarete von Wrangell: Brave & determined

Even as a little girl, Margarete von Wrangell was different. Daisy, as she was nicknamed, charted her own path from an early age.

In a letter, her mother wrote: “The night before, the storm had broken many old trees in the park, blocking our path. Daisy did not want to follow my advice and, like me, look for detours. She thought it wasn’t fun and too tiring to always walk around, so she climbed over all the tree trunks. When there were none left, she sadly called out to me: ‘Now there are no obstacles left!'”

Was Margarete von Wrangell just an exception?

Little Margarete was born on the second day of Christmas in 1876. Her parents, the Russian General Baron Karl Fabian von Wrangell (1839–1899) and his wife Julie Ida Marie von Wrangell, belonged to the Baltic-German nobility with considerable land holdings. Margarete was their third child, and they translated the flower name Margerite into English and named their child Daisy.

From a young age, Daisy not only learned several languages but also lived in various cities due to her father’s relocations as an officer – first in Moscow, later in Reval, today’s Tallinn. In noble circles, it was customary for children to receive private instruction. Thus, Margarete read famous writers like Homer and Virgil in the original, wrote short stories, and engaged in painting. She had many interests.

When the family moved to Reval, Margarete attended a German girls’ school. Natural science and philosophy were among her favorite subjects. But above all, she was interested in mathematics. In 1894, she passed the teaching exam with distinction and subsequently worked for a few years as a private teacher for natural sciences.

And she knew how to assert herself.

„Daisy is quite different. She has a very reformative nature. If you gave her a task, even with instructions on how it should be done, she would only clearly ask what needed to be done, not how it should be done, and thus had an improvement in mind. (…)

Over the years, Daisy’s peculiar way of intervening has developed more and more, making her a person of initiative, discovery, and progress, earning her the respect of many.nstructions on how it should be done, she would only clearly ask what needed to be done, not how it should be done, and thus had an improvement in mind. (…)“

Julie Ida Marie von Wrangell

Against the current

Although Margarete von Wrangell had a strong character, she was not immune to crises. Perhaps it was because she lost her grandfather, father, and both sisters in a short span of time, who died in the years 1888 and 1889.

She wrote to a friend: “I tried religion. Then I tried philosophy; all empty intellectual propositions and never a little bit of life or benefit from it. So this is the life one looked forward to? Is there really nothing gripping, alive, worth living for?” Margarete von Wrangell suffered from depression.

Yet she always knew what she wanted. Or what she didn’t want. “Marrying is good – not marrying is better.” But that was precisely the path many young women took. Their education ended after school, they looked for a “good match,” got married, and became housewives. Studying was out of the question for most women. In Württemberg, girls were only allowed to take the Abitur (university entrance exam) from 1893 onwards – but that was a prerequisite for studying.

Perhaps it was her brother Nikolai who encouraged her on her path. A few years earlier, he had fulfilled his dream and enrolled in a chemistry course in Zurich. Margarete admired him and always described how diligently he studied. But then Nikolai fell ill with tuberculosis and died before he could complete his studies. Was it his fate that sealed Margarete’s decision?

We don’t know, but in 1903 Margarete von Wrangell secretly attended a botanical summer academy at the University of Greifswald. She disguised her stay there as a visit to a sanatorium. Afterwards, her decision was clear: she wanted to study. However, since she only had a teaching diploma from Reval, which was not recognized in Germany for university studies, she could only enroll as an auditor. The University of Tübingen was among the first to allow women to study, and Margarete von Wrangell began her studies in chemistry and botany there at the age of 27 – to general astonishment.

Together with her mother and aunt, Margarete moved to Tübingen. However, she was not a typical student. As a noblewoman, she moved in high society, rode horses, played tennis, and even undertook a bicycle tour to Venice. When her mother and aunt returned to Estonia, she got a roommate. Her friend from Reval, Ebba Husen, now shared the apartment with her. Thus, Margarete von Wrangell led a life that was very unusual for women of her time.

„All our relatives and the wide circle of our acquaintances and friends persisted in their belief that it was a ‘fixed idea’ and still considered our move to Tübingen a fanciful venture.“

Margarete von Wrangell

Studying with Noble Prize winners

The Scottish chemist William Ramsay (1852-1916)

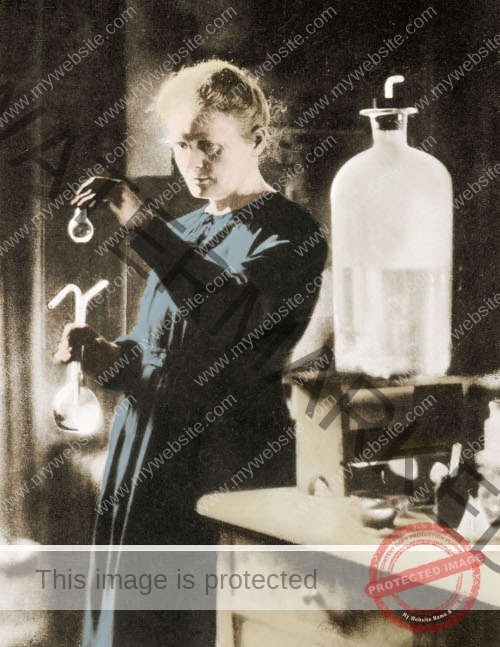

Physicist and chemist Marie Curie (1867-1934)

How does a young scientist get to know the scientific celebrities of her time? By going on a journey. After passing her chemistry exam, Margarete von Wrangell spent a semester in Leipzig and finally earned her doctorate in 1909 with summa cum laude under Professor Wislicenus in Tübingen. Her topic was: “Isomerism phenomena in formylglutaconic acid ester and its bromine derivatives.”

Now it was time to build contacts. Margarete von Wrangell’s path led her as an assistant to the Agricultural Experimental Station in Dorpat and eventually to two Nobel Prize winners. In 1910, she researched alongside William Ramsay in London in the field of radioactivity and, after a detour to Strasbourg, she worked for several months in 1912 with Maria Skłodowska-Curie in Paris.

“I work with 100 liters of uranium, an amount that could fill two wine barrels. Madame Curie entrusted me with this treasure, telling me that this work was of particular personal interest to her and that such an amount of uranium existed in the world only with her.”

When Margarete von Wrangell was offered the leadership of the experimental station of the Estonian Agricultural Association in Tallinn, she agreed. There, she inspected seeds, feed, and fertilizers until the Russian October Revolution broke out, and Russian soldiers stood at the gates of the institute. However, Margarete von Wrangell refused to hand over the institute and was arrested. She spent several weeks in prison. Only in the spring was she freed by German soldiers and left for Germany permanently.

Why Margarete von Wrangell came to Hohenheim

It was Lieutenant Hermann Warmbold, a friend of her father’s, who ultimately brought the young scientist to Hohenheim. Her research met great interest here. Through experiments, Margarete von Wrangell discovered that some plants could better absorb poorly soluble soil phosphates when the soil was mixed with an acidic fertilizer.

Together with Friedrich Aereboe, the scientist developed a fertilization system that became known as the “Aereboe-Wrangell Fertilization System.” With this, Margarete von Wrangell gave new impetus to the agricultural chemistry founded by Justus Liebig. This caught the attention of the fertilizer industry. After World War I, Germany had to import phosphorus, a component of fertilizer, at a high cost from abroad. Margarete von Wrangell’s research suggested that high crop yields could be achieved even with low imports if potash, nitrogen, and iodine were present in the soil in sufficient amounts.

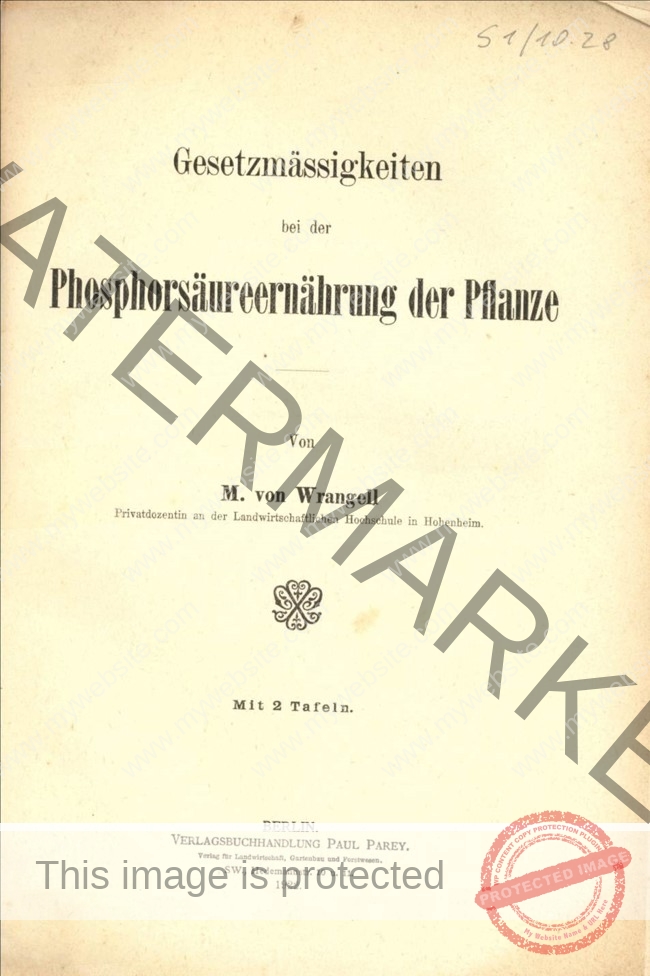

Immediately after her habilitation in 1920 on the “Regularities in the Phosphoric Acid Nutrition of Plants,” she received an extraordinary offer from the industry: The fertilizer industry promised the government a whopping 75 million Reichsmarks to establish an Institute for Plant Nutrition – on the condition that Margarete von Wrangell would be appointed as the professor in charge.

But Nobel laureate Fritz Haber, who during World War I had succeeded in the large-scale synthesis of ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen at the Physical-Chemical Institute of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Berlin, also noticed Margarete von Wrangell in 1922. He tried to recruit her as a permanent staff member for his institute and became one of her supporters.

Margarete von Wrangell wrote to her mother:

Hohenheim Institute for Plant Nutrition

Habilitation of Margarete von Wrangell

„The North reaches out its hands to me, the South wants to keep me. I try to gain something from the situation. Not money or titles, but rather the most favorable working conditions for myself.“

Margarete von Wrangell

The only women among professors

The negotiations were tough. A woman as a professor – moreover, the first in Germany! Many professors at the conservatively oriented Hohenheim University couldn’t imagine it. Resistance quickly arose in the university senate. Some openly doubted whether a woman could lead an institute with predominantly male staff.

However, Margarete von Wrangell used her contacts, and the financiers threatened to establish the institute elsewhere. This threat was the breakthrough. Margarete von Wrangell was appointed as a professor of plant nutrition at the Agricultural College of Hohenheim.

But the criticism did not subside. The professors in Hohenheim resented her for being appointed without a proper appointment procedure. And the agricultural chemist Paul Ehrenberg confronted her with allegations of plagiarism. His accusation: Margarete von Wrangell had used Russian works in her habilitation without citation. These disputes had no legal consequences, and the allegations fizzled out.

Margarete von Wrangell indeed had a tough time. Perhaps that’s why she appeared “brusque” and “domineering” because she had to assert herself in a male-dominated environment. In any case, her relationship with her colleagues was not easy, and although she was attributed with a sense of humor, she was considered arrogant.

In a letter to her mother in 1923, she wrote: “I have many battles in my profession. I am the first tenured female professor in Germany. Moreover, I have been publicly recognized by some scientific luminaries. This has earned me the hostility of many; but my institute is a creation that will remain of lasting value and benefit, and despite great worry and workload, it still brings me joy. In any case, I know what I’m fighting for.”

Nevertheless, Margarete von Wrangell was extraordinarily successful in her research. She published numerous articles in professional journals and supervised 16 doctoral students. She also was involved in the German Association of Academic Women and was a member of its first board. At the age of 51, she finally decided to do what she had always rejected.

Margarete von Wrangell 1930

Why Margarete von Wrangell finally walked down the aisle

At the age of 51, Margarete von Wrangell married her childhood friend and cousin, Wladimir Prince Andronikow. Was it true love? Or did she just want to help a relative in need and escape loneliness? We will probably never know the real reasons.

In a letter, she wrote to Prince Andronikow: “I have no desire to travel alone. At the end of July, I am going to Holland for ten days for an international congress of academic women, as a delegate from Germany. Please give me an answer beforehand.”

Apparently, she enjoyed the company of Prince Andronikow. However, she couldn’t get married without a special ministerial exemption. At that time, women were dismissed from civil service after marriage and had to give up their profession. But Margarete von Wrangell didn’t want that at all.

She received the special permission and continued working at her institute. However, she didn’t have much time left with her husband. In March 1932, she died at the age of 55 from a kidney ailment, after successfully leading the Plant Nutrition Institute in Hohenheim for a decade.

The Legacy of Margarete von Wrangell

A successor in the professorial college was a long time coming. It wasn’t until 1974 that Leonore Blosser-Reisen, in the field of Economics, became a full professor at the University of Hohenheim. In the agricultural sector, specifically in the field of soil biology at the Institute of Soil Science and Land Evaluation, Ellen Kandeler was only appointed as the next professor in 1998.

Margarete von Wrangell has not been forgotten to this day – her name lives on. Streets are named after her in the Wolfgang Technology Park in Hanau, in the Steckfeld district of Stuttgart near the University of Hohenheim, and in Heide near the West Coast University of Applied Sciences.

And two support programs bear her name in support of young female scientists. The Margarethe von Wrangell Foundation e.V. promotes cooperation between university institutes and small and medium-sized enterprises.

The Margarete von Wrangell Fellowship Program, which was announced by the state of Baden-Württemberg from 1997 to 2022, encouraged qualified female scientists to habilitate and supported them for five years.

Curriculum Vitae of Margarete von Wrangell

7 January 1877

Born 07.01.1877 in Moscow

1894

Graduation from the Howensche School in Reval (Estonia) with "excellent", followed by a teaching examination

1904-1909

Studied Botany and Chemistry from 1904-1909 in Tübingen and Leipzig

1909

Ph.D. (rer. nat.) in 1909 on "Isomerism phenomena in Formyglutaconic acid ester and its Bromine derivatives" summa cum laude under Professor Wilhelm Gustav Wislicenus

1909

Assistant at the Agricultural Experimental Station in Dorpat

1910

Worked with William Ramsay in London in the field of radioactivity

1911

Assistant at the Institute for Inorganic and Physical Chemistry at the Kaiser Wilhelm University in Strasbourg

1912

Research with Maria Skłodowska-Curie in Paris

From 1912

From 1912, headed the Experimental Station of the Estonian Agricultural Association in Reval

1918

Arrested by the Bolsheviks, rescued by German soldiers, and emigrated to Germany

From 1918

From 1918 in Hohenheim at the Agricultural Experimental Station

1920

Habilitation in 1920 on "Laws of Phosphoric Acid Nutrition in Plants"

1922-1923

Research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin-Dahlem

1923

Called to the Agricultural College in Hohenheim, full professorship for Plant Nutrition. As a professor and institute director, she supervised 16 doctoral theses, numerous lucrative third-party projects for the industry, and brought Hohenheim to international renown.

1926

Married Prince Vladimir Andronikow

31 March 1932

Died 31.03.1932 in Stuttgart

Sources

„Margarethe von Wrangell – The Life of a Woman 1876 – 1932“ from diaries, letters, and memories presented by Prince Wladimir Andronikow, 1936, Alber Langen / Georg Müller Verlag, Munich

„Margarete von Wrangell and other pioneers – The first women at the universities of Baden and Württemberg“ by U. Fellmeth and H. Winkel 1998, Scripta Mercaturae Verlag, University of Hohenheim Archive