A transformation at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences in Hohenheim?

What has changed at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences 100 years later?

Initially, remarkably little. For 75 years after Margarete von Wrangell, no woman was appointed as a full professor at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences. It’s important to understand that there are only eight universities in Germany offering agricultural science programs. Since only external scientists can be appointed to professorships, the pool is small, and the proportion of female applicants is even smaller. As a result, agricultural sciences remain a male-dominated field.

The 1990s nearly marked the end of the University of Hohenheim. Due to declining student numbers, there was consideration of merging the Universities of Hohenheim and Stuttgart. After the baby boomers who entered university in the 1980s, student numbers dropped significantly due to the “pill gap.” After much debate, the merger idea was abandoned. Nonetheless, the University of Hohenheim had to face societal changes.

Because the state higher education law set a minimum size for faculties in 2005, the deans merged Faculty III for Plant Sciences and Faculty IV for Animal Sciences, Agricultural Engineering, and Agricultural Economics into a single Faculty of Agricultural Sciences.

Simultaneously, the Bologna Process brought the switch from diploma to bachelor’s and master’s programs to make the degrees internationally recognized and comparable.

In the 1999/2000 academic year, the Master’s in Agricultural Sciences was offered for the first time. More international students also came to Hohenheim again—after all, the university has ranked first in Germany for agricultural sciences for many years. After the turn of the millennium, further restructurings took place, and in 2010 the Plant Nutrition Institute was merged with the three institutes of Fruit, Wine, and Vegetable Cultivation (370), Plant Nutrition (330), and Crop and Grassland Science (340) to form today’s Institute of Crop Science.

But what about women in leadership positions at the agricultural faculty? Was Hohenheim ahead of other universities with its former institute founder?

Not at all. There were a few private lecturers and associate professors, but none held their own chairs. It wasn’t until April 1998 that Ellen Kandeler, from the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, was appointed as Professor of Soil Biology, directly succeeding Margarete von Wrangell. This was despite more than 130 professors being given their own chairs during the same period.

Between 1923 and 1998, three women habilitated at Faculty III for Plant Sciences, with Otti Zeller in Fruit and Vegetable Cultivation and Anette Fomin in Plant Ecology and Ecotoxicology also being granted teaching authorization and thus the title of private lecturer. At the age of 35, Anette Fomin became the youngest private lecturer in the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences to date.

An upward trend is only noticeable after the turn of the millennium. In 1999, a year after Ellen Kandeler, Anne Valle Zárate became a full professor in Animal Husbandry. After her, from 2001 to 2023, five junior professors and 13 full professors were appointed—during the same period, three men received junior professorships, and 45 scientists were appointed as full professors. Thus, in Hohenheim, the proportion of women was about one-third, in line with the national average.

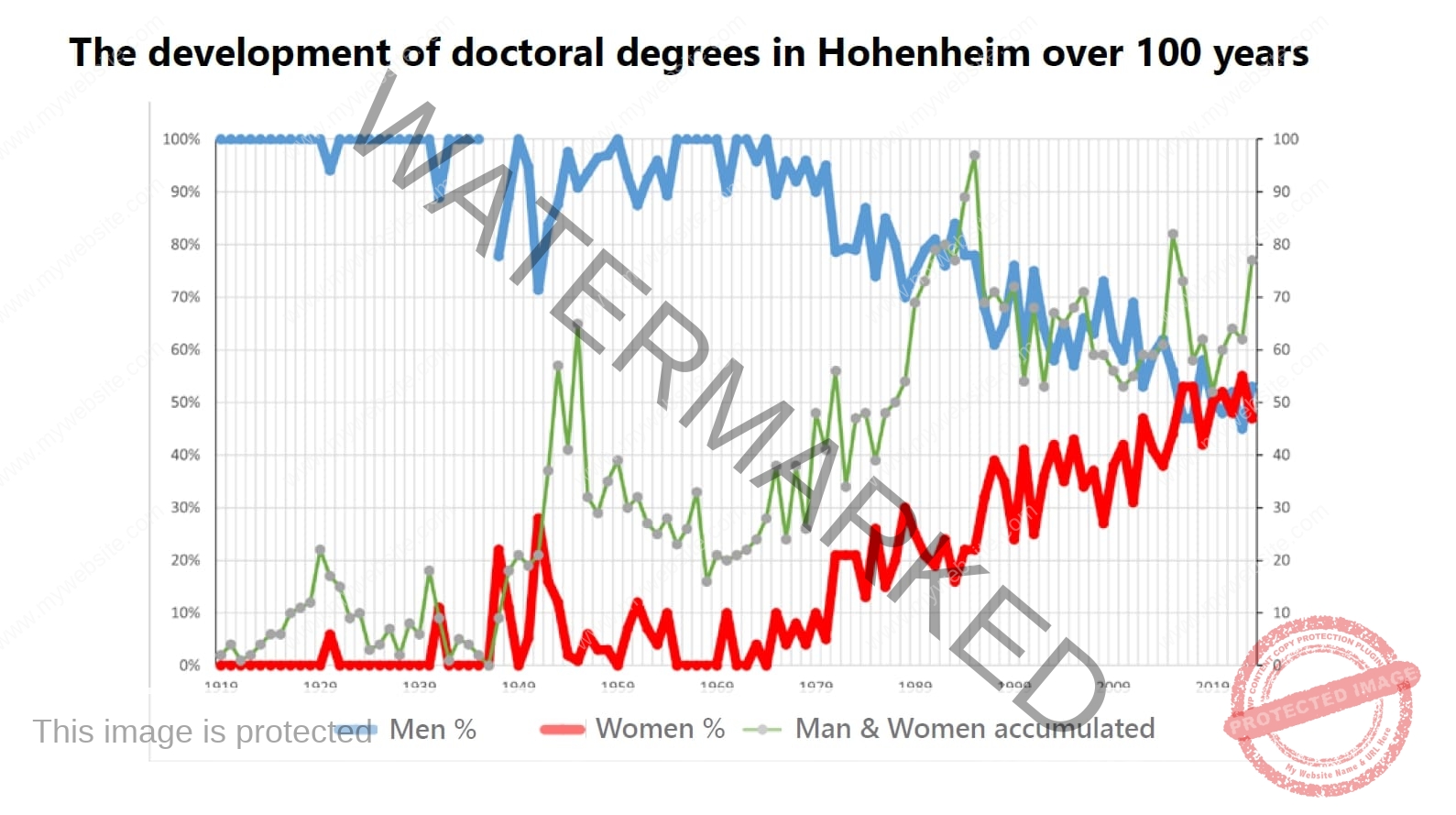

Especially from 2010 onwards, there was a significant upward trend. This was likely due to the increasing number of female students and doctoral candidates at both Hohenheim and the other seven universities offering agricultural science programs. In 2016, for the first time, there was gender parity in completed doctorates at the University of Hohenheim (see figure).

As a result, more qualified women—including those from abroad—applied for advertised professorships. Significant contributors to this were the Federal Ministry of Education and Research’s Professorship Program I to III, the newly introduced junior professorships, and the Wrangell Fellowship. Most former Wrangell Fellows from the University of Hohenheim are now professors at other universities or have pursued junior professorships. This demonstrates the importance of funding programs for driving change.

Despite these successes, Professor Martina Brockmeier, President of the Leibniz Association, former chair of the German Council of

Science and Humanities, and since 2009, Professor of International Agricultural Trade and Food Security at the University of Hohenheim (on leave), warns:

“In my opinion, the development of a university also significantly depends on the stronger representation of women in university committees. We know that committees only respond to a heterogeneous composition when both genders make up at least 30% each.” Martina Brockmeier, who herself became the first dean of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences in 2012, speaks from experience. As the former chair of the German Council of Science and Humanities, she also reports that “with gender-balanced committees, significantly different and, in my opinion, better decisions are made.”

Therefore, it should be a priority at Hohenheim and every university to encourage female scientists to participate as prorectors,

senators, chancellors, or members of the university council. After all, they have a say in the appointment of professorships and thus set the course for the future.

Female successors of Margarete von Wrangell at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences

Prof. Margarete von Wrangell

Plant Nutrition

Appointed on January 1, 1923

Prof. Ellen Kandeler

Soil Biology

Appointed on April 1, 1998

Prof. Anne Valle Zárate

Animal Nutrition and Rangeland Management in

the Tropics and Subtropics

Appointed on April 1, 1999

(retired)

Prof. Eva Barlösius

Gender and Nutrition

Appointed on August 1, 2004

(accepted external appointmnt later)

Prof. Anne Bellows

Gender and Nutrition

Appointed on August 1, 2007

(accepted external appointment later)

Prof. Martina Brockmeier

International Agricultural Trade and Food Security

Appointed on August 1, 2009

(on leave, currently President of the Leibnitz Association)

Prof. Iris Lewandowski

Biobased Resources in the Bioeconomy

Appointed on February 1, 2010

Prof. Regina Birner

Social and Institutional Change in Agricultural Development

Appointed on October 1, 2010

Prof. Andrea Kruse

Conversion Technologies of Biobased Resource

Appointed on March 20, 2012

Prof. Uta Dickhöfer

Animal Nutrition and Rangeland Management in the Tropics and Subtropics

Appointed on June 1, 2012

(accepted external appointment later)

Prof. Andrea Knierim

Communication and Advisory Services in Rural Areas

Appointed on April 1, 2013

Prof. Claudia Bieling

Societal Transition and Agriculture

Appointed on April 1, 2015

Prof. Korinna Huber

Functional Anatomy of Livestock

Appointed on June 1, 2015

Prof. Katja Nowick

Bioinformatics

Appointed on January 1, 2016

(accepted external appointment later)

Prof. Christine Wieck

Agricultural and Food Policy

Appointed on February 1, 2018

Prof. Jana Seifert

Functional Microbiology of Livestock

Appointed on January 1, 2019

Prof. Simone Graeff-Hönninger

Agronomy

Appointed on October 1, 2022

Prof. Amélia Camarinha da Silva

Livestock Microbial Ecology

Appointed on December 1, 2023

Prof. Sandra Schmöckel

Physiology of Yield Stability

Appointed on May 1, 2024

Since when have habilitations existed in Germany?

The habilitation, as a qualification path for a university professorship, has a long tradition in Germany and dates back to the 19th century. It‘s challenging to pinpoint an exact founding year since the development of university systems evolved gradually over time.

The core idea behind the habilitation is that, following a PhD, researchers demonstrate their qualification for a professorship through further independent research achievements and teaching experience. In Germany, the habilitation has been and continues to be a crucial requirement for obtaining teaching authorization at universities.

In recent years, German universities have revised their habilitation regulations or introduced alternative career paths, such as the junior professorship with a tenure track system. Despite these changes, habilitation remains an important qualification route for attaining a professorship at many universities.

“In my opinion, anessential aspect of a university’s development is the stronger representation of women in its governing bodies.”

Martina Brockmeier

the first dean of the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences in 2012

What is a full professorship?

A full professorship, often simply referred to as a „professorship,“ is a permanent, tenured position at a university or higher education institution. In Germany and many other countries, the term „full“ indicates that the position is permanently filled and comes with stable working conditions and leadership responsibilities.

A full professorship is typically the highest rank in the academic hierarchy. The professor enjoys significant academic freedom in teaching and research and often takes on leadership roles in university administration.

Appointment to a full professorship is based on outstanding academic achievements and experience in both research and teaching.

The exact title and requirements for full professorships vary by country. For example, in Germany, there is a distinction between W2 and W3 professorships, with W3 positions generally offering higher pay and more responsibilities.

What is an associate professorship?

An associate professorship (or extraordinary professorship) is a special type of position at a university, indicating that the individual does not hold a full chair. The exact meaning and structure of such positions can vary depending on the country and university system.

Key characteristics of an extraordinary professorship:

1. Academic recognition: Appointment to an extraordinary professorship is usually based on outstanding academic achievements and experience. It may also indicate that the individual has notable qualifications from practical or industrial work.

2. Temporary nature: An extraordinary professorship can be a temporary position, often because the individual is simultaneously engaged in other scientific or industrial activities.

3. Research focus: These positions are often more research-oriented, with the professor holding specialized expertise in a particular field.

4. Teaching obligations: While extraordinary professors do have teaching responsibilities, they typically have a lighter teaching load compared to full professors.

What is a junior professorship with tenure track?

The „junior professorship with tenure track“ is a relatively new career path in the German higher education system, designed to support talented early-career researchers and offer them a clear path to a permanent professorship. The tenure-track model originates from the Anglo-Saxon academic system.

This model aims to increase the attractiveness of the German academic system for promising young scientists while also improving the quality of research and teaching at universities. After a successful evaluation period, junior professors on a tenure track can transition to a permanent professorship, providing a secure career progression.

The key characteristics of a junior professorship with tenure track:

1. Junior Professorship: The junior professorship is a temporary position for early-career researchers, allowing them to conduct independent research and gain teaching experience.

2. Tenure Track: The term „tenure track“ refers to a defined career path with clear criteria and evaluations. During the tenure track process, the performance of the junior professor is regularly assessed.

3. Tenure: If the junior professor meets the required performance standards, they are typically offered a permanent professorship (tenure). Tenure means the position is no longer temporary, providing the researcher with long-term job security at the university.

4. Promotion of Research and Teaching: The goal of the tenure track model is to promote excellence in research and teaching while offering outstanding early-career researchers a clear path to a permanent professorship.

What professors have to do with doctoral studies

Without a university professor, there is no doctoral project: this was true in the past and still applies today. Just like teaching, the supervision of young researchers during their PhDs and habilitations is part of the Humboldtian ideal of education for a professor.

Generally, anyone with a good master’s degree can pursue a PhD. The specific requirements are outlined in the doctoral regulations of each university. There are also rules for the academic supervision of a PhD. This role can be fulfilled by a doctoral advisor (often

referred to as a “doctoral mother” or “doctoral father”) or a supervisory team.

The faculties and departments determine who is eligible to supervise PhD students. Typically, these include professors, junior professors, as well as private, university, or academic lecturers at the university or an institution authorized to grant PhDs.

Cooperative arrangements are also possible, in which professors from universities of applied sciences or universities of applied sciences participate.

Under Margarete von Wrangell, a total of 16 PhD students completed their doctoral projects. During this time, she served as the primary advisor 12 times and as a co-advisor four times (according to the Doctoral Register of Agricultural Sciences).

Her first PhD student, Ludwig Meyer, defended his dissertation on February 19, 1926, three years after von Wrangell’s appointment, with the title “Studies on Root Solubility and the General Solubility Conditions of Soil Phosphoric Acid,” earning the distinction “with honors.”

The number of supervised PhDs at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Hohenheim steadily increased over more than 100 years (see figure). There is now parity between male and female PhD graduates.

A significant proportion of PhD supervisions have been carried out by the female professors appointed after von Wrangell. Since 2015, more than 130 PhD projects have been supervised and successfully completed by female professors currently working in Hohenheim as the primary academic advisor.

The development of doctoral degrees in Hohenheim over 100 years

Qualification steps after a PhD

1. PhD: Attainment of a doctoral degree (e.g., Dr. rer. nat., Dr. agr., Ph.D., or similar).

2. Habilitation Thesis: An independent scientific work that contributes to research, typically written in a specific field.

3. Publications: In addition to the habilitation thesis, researchers must demonstrate their research achievements through scientific publications.

4. Habilitation Lecture: A public lecture on the research, presented as part of the habilitation colloquium.

5. Teaching Authorization with Private Lectureship: In many cases, candidates must demonstrate their teaching abilities through evaluated lectures or other teaching activities as part of the habilitation process.

Habilitation and teaching authorization associated with private lectureship

In Germany, the habilitation is an academic qualification process that takes place after the completion of a PhD, or the awarding of a doctoral degree. During the habilitation, researchers conduct independent research and publish scholarly works in a specialized field. The habilitation is generally a prerequisite for a professorship at a university. The specific requirements for habilitation can vary depending on the university and the field of study.

After successfully completing the habilitation, a researcher can pursue teaching authorization along with the title of „Privatdozent“ (PD). This requires a separate examination. A Privatdozent is then authorized to give lectures and conduct examinations. Privatdozents are required to teach but are not typically employed on a permanent basis; they work independently and are also permitted to supervise PhD students.

The academic qualification of university lecturers is not only required in the DACH countries (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland), but also in other European countries. In particular, in Central and Eastern European countries like Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, and Russia, as well as in Finland and Sweden, habilitation is a prerequisite for university teaching.

In many other countries, a state-certified additional qualification replaces the habilitation, such as in Denmark and the Netherlands. In France, the Habilitation à diriger des recherches (HDR) has once again become the central qualification for obtaining a professorship.

Research by Annette Fomin